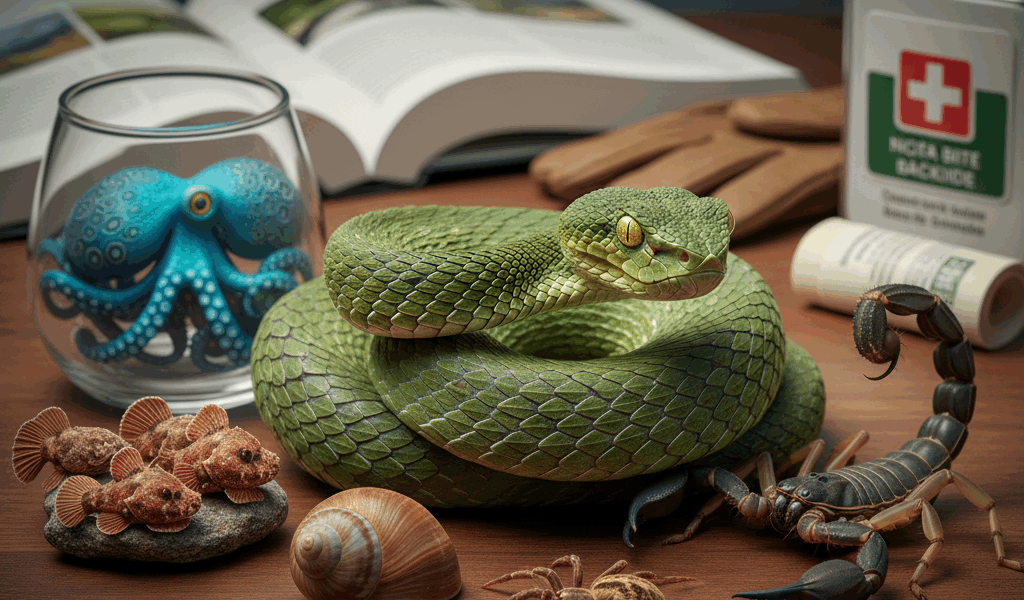

Venomous animals has gotten complicated with all the misinformation flying around. As someone who spent years doing fieldwork in places where a wrong step could land you in the ER (or worse), I learned everything there is to know about which critters can actually hurt you and how to avoid them. Today, I will share it all with you.

Look, I’m not going to sugarcoat it — some of these animals are genuinely terrifying. But here’s the thing most people get wrong: the vast majority of venomous species want absolutely nothing to do with us. Most bites and stings happen because someone accidentally cornered an animal or stepped where they shouldn’t have. So let’s walk through the big ones, where they live, what their venom does, and most importantly, how you keep yourself safe.

Wait — Venomous or Poisonous? There’s a Difference

Probably should have led with this section, honestly. People mix these up constantly, and it matters more than you’d think. Here’s the quick version: venomous animals inject their toxins into you — think fangs, stingers, barbs. Poisonous animals are the ones you get hurt from by touching or eating them. So a rattlesnake? Venomous. It bites you and injects venom through its fangs. A poison dart frog? Poisonous. You absorb toxins through your skin if you handle it.

Now here’s where it gets really interesting (at least to a nerd like me). Venom isn’t just one thing. It’s this incredibly complex cocktail of proteins, enzymes, and peptides, and it varies wildly between species. I’ve even read studies showing the same species can have different venom compositions depending on where they live geographically. That’s wild, right? This is also why identifying what bit you is so critical for medical treatment — docs need to know exactly what they’re dealing with to give you the right antivenom.

Venomous Snakes — The Ones That Kill the Most People

Snakes. They’re the big one. No other venomous animal group comes close in terms of human fatalities. We’re talking somewhere between 81,000 and 138,000 deaths every single year worldwide. That number still shocks me every time I see it. The vast majority of those deaths happen in rural parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America where getting to a hospital with antivenom just isn’t realistic.

North American Pit Vipers

The US has roughly 20 venomous snake species, and pit vipers are the headliners. That includes rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths (water moccasins, if you’re from the South). They all share this cool feature — heat-sensing pits between their eyes and nostrils that let them detect warm-blooded prey. It’s basically built-in thermal imaging. Nature is insane sometimes.

The Western Diamondback Rattlesnake is the one responsible for more snakebite deaths in North America than any other species. You’ll find them all across the southwestern states and into Mexico. These are big snakes — we’re talking six feet or more — and they don’t mess around with venom delivery. Their hemotoxic venom goes after your red blood cells and destroys tissue. The bite site swells up fast, hurts like nothing you’ve felt before, and can develop necrosis if you don’t get treated.

Then there’s the Timber Rattlesnake, hanging out in eastern forests from Minnesota down to Texas and up through New England. Here’s what surprises people: despite packing serious venom, these guys are actually pretty chill. Remarkably docile, really. They almost never bite unless you literally step on one or grab it. The Mojave Rattlesnake, though? Different story in terms of venom. It’s probably got the most dangerous venom of any North American snake because it hits you with both hemotoxic AND neurotoxic components. That neurotoxic part can cause respiratory failure. Not great.

Asian Cobras and Kraits

Southeast Asia is ground zero for venomous snake encounters. The concentration of dangerous species there is unmatched anywhere else on the planet. Indian Cobras and their relatives kill tens of thousands of people every year across the Indian subcontinent. Their venom is primarily neurotoxic, meaning it attacks your nervous system. Progressive paralysis sets in, and if it reaches the muscles controlling breathing, you’ve got hours at best without treatment.

The King Cobra deserves its own paragraph because, well, it’s the King Cobra. Over 18 feet long in some cases — the longest venomous snake in the world. I remember the first time I saw one in the wild during a research trip. My heart basically stopped. But here’s the thing most people don’t know: King Cobras are actually pretty reclusive. They avoid humans when they can. Bites are relatively rare. When they do bite, though, the sheer volume of venom they pump in can be fatal incredibly fast without antivenom.

Kraits freak me out more than cobras, honestly. They hunt at night and have this habit of slipping into homes looking for shelter. The Common Krait and Banded Krait cause a ton of deaths in South Asia, and here’s the worst part — people get bitten in their sleep and don’t even realize it until symptoms show up hours later. The bite itself barely hurts. You might not wake up from it. That’s genuinely nightmarish.

African Mambas and Vipers

Africa has some absolutely legendary venomous snakes. The Black Mamba is the one everyone’s heard of, and for good reason. This snake can strike at speeds over 12 miles per hour and delivers neurotoxic venom that can kill you within hours if untreated. Fun fact that I love telling people: the Black Mamba isn’t actually black on the outside. It’s gray-brown. The “black” comes from the inside of its mouth, which it shows off during threat displays. Pretty metal, honestly.

But the Puff Adder is the real killer on the continent in terms of raw fatality numbers. It’s not because its venom is the strongest — it’s because of behavior and distribution. Puff Adders are everywhere, they’ve got incredible camouflage, and when you walk near one, it doesn’t slither away like most snakes would. It just sits there. Motionless. So people step right on them. That’s what makes venomous wildlife endearing to us researchers — the survival strategies are so perfectly evolved, even when they’re working against us humans.

Australian Elapids

Australia. Of course. The continent that seems designed to test human survival at every turn. It’s home to a ridiculous number of the world’s most venomous snakes. The Inland Taipan takes the crown for most toxic venom on Earth — a single bite contains enough venom to kill over 100 adult humans. Let that sink in. But here’s the kicker: this snake lives in such remote areas and is so shy that no confirmed human fatalities have ever been recorded from it. Zero.

The Eastern Brown Snake is the one Australians actually need to worry about. It causes more snakebite deaths in Australia than any other species. Why? Because it lives near people, it’s fast, and it’s not exactly the most patient snake when it feels threatened. Its venom causes progressive coagulopathy — basically your blood loses the ability to clot, which leads to uncontrollable bleeding. Really nasty stuff.

Venomous Spiders That Actually Matter

I know, I know — everybody’s terrified of spiders. But can I be real with you for a second? The fear is massively disproportionate to the actual risk. Only a handful of spider species worldwide can genuinely hurt a human. Most spider venom evolved to take down insects and is basically useless against something our size. That said, there are a few you absolutely need to know about.

Black Widow Spiders

Black widows are found across temperate and tropical regions all over the world — North America, South America, Europe, Africa, Australia. The females are the ones to watch for, with that iconic red hourglass marking on a shiny black belly. Pretty hard to miss once you know what you’re looking at.

Their venom contains something called latrotoxin, and it’s a potent neurotoxin. A bite triggers severe muscle cramps, abdominal rigidity (your stomach muscles lock up like a board), heavy sweating, and spiked blood pressure. Sounds terrible, and it is — incredibly painful. But fatal? Rarely, at least in healthy adults. Kids, older folks, and people with existing health conditions face higher risk. The good news is there’s antivenom available and it works well when given quickly.

Brown Recluse Spiders

The Brown Recluse lives in the central and southern US. It builds messy, irregular webs in places that don’t get disturbed much — closets, attics, storage boxes. You know, the places where you shove stuff and forget about it for months. It’s a small, tan-colored spider with a violin-shaped marking on its back. Hence the nickname “fiddleback.”

Here’s where it differs from the black widow in a pretty significant way. Instead of systemic neurotoxic effects, brown recluse venom contains enzymes that literally destroy tissue at the bite site. In bad cases, you get these necrotic ulcers that keep expanding over days or even weeks. Some require surgery. There’s also something called systemic loxoscelism where the venom causes your red blood cells to break down and organs get damaged. That’s rare but it can be life-threatening when it happens.

Australian Funnel Web Spiders

Sydney Funnel Webs are the real deal. These are big, aggressive spiders — not shy at all — that build funnel-shaped webs in moist, sheltered spots around southeastern Australia. The males are actually the more dangerous ones, which is unusual. They wander around looking for mates during warm weather and that’s when most serious envenomations happen.

Their venom contains atracotoxin and it works fast. We’re talking profuse salivation, muscle spasms, blood pressure spikes, and potentially fatal pulmonary edema. Before they developed the antivenom back in 1981, these spiders killed a number of people. Since then? Not a single death when antivenom was given in time. Modern medicine for the win.

Scorpions — Don’t Sleep on These Guys

There are roughly 2,500 scorpion species out there, living on every continent except Antarctica. But before you panic, only about 25 to 30 of those species are genuinely dangerous to humans. Here’s a handy (though not foolproof) rule of thumb I picked up early on: scorpions with big pincers and skinny tails tend to be less dangerous. The ones with tiny pincers and fat tails? Those are the ones relying on venom to do the heavy lifting. That’s when you worry.

In North America, the Arizona Bark Scorpion is your main concern. It can cause serious neurotoxic effects — numbness, breathing difficulty, muscle spasms. Deaths are rare with modern medical care but they can happen, especially in young children or elderly people.

Globally, the Deathstalker Scorpion (and yeah, that’s its real name — sounds like a movie villain) lives in North Africa and the Middle East. Extremely potent neurotoxic venom. It’s behind most scorpion deaths in its range. Fat-Tailed Scorpions across Africa and Asia are similarly dangerous, and the fatality rates are higher in areas where healthcare access is limited. Seeing a pattern here? Access to medical care is often the deciding factor between surviving an envenomation and not.

Marine Stingers and Venomous Jellyfish

The ocean has its own roster of venomous nightmares. Jellyfish and their relatives cause thousands of envenomations every year, and while most are just painful, some can straight up kill you. I’ve been stung a few times over the years — nothing serious, thankfully — but it definitely makes you respect the water differently.

Box Jellyfish

Australian Box Jellyfish are among the most venomous creatures on the entire planet. Not just in the ocean — on Earth, period. Contact with their tentacles triggers immediate, excruciating pain and can cause cardiac arrest within minutes. Minutes. Their tentacles are covered in millions of nematocysts — tiny capsules that fire barbed tubules into your skin and inject venom on contact.

Chironex fleckeri, also called the Sea Wasp, has killed over 60 people in Australian waters since 1883. Even small specimens can deliver lethal envenomations, which is a terrifying thought. If you or someone gets stung, pouring vinegar over the area can stop unfired nematocysts from discharging. But it does nothing for venom that’s already been injected. You still need emergency medical care immediately.

Portuguese Man-of-War

Here’s something that blows people’s minds: the Portuguese Man-of-War isn’t actually a jellyfish. It’s a colonial organism — basically a floating city of specialized organisms called zooids all working together. That blue balloon-like float trailing long tentacles? That’s not one animal. It’s thousands. You’ll find them in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Stings are rarely fatal but they hurt like absolute hell. Intense pain, raised welts, and sometimes systemic symptoms like fever and shock. Not a fun beach day.

Irukandji Jellyfish

These ones mess with my head. Some Irukandji jellyfish are barely bigger than your fingernail. Tiny. And the initial sting seems like nothing — minor discomfort at most. Then, 20 to 30 minutes later, Irukandji Syndrome hits you like a freight train. Severe back pain, muscle cramps, sweating, nausea, a feeling of impending doom (that’s an actual clinical symptom, by the way), and dangerously high blood pressure. People have died from these little things. Don’t let the size fool you.

Venomous Fish and Other Marine Creatures

Plenty of fish carry venomous spines for self-defense. Most just cause localized pain and swelling — not fun, but not dangerous. A few, though, can land you in serious trouble.

Stonefish

The Stonefish is the most venomous fish on Earth. Let me paint the picture for you: it lives in shallow coastal waters across the Indo-Pacific region, and it looks exactly like an encrusted rock sitting on the seafloor. Perfect camouflage. You literally cannot tell it’s there. It’s got 13 dorsal spines loaded with venom that fire when pressure is applied — like, say, when an unsuspecting swimmer steps on what they think is a rock.

People who’ve been stung describe the pain as the worst thing they’ve ever experienced. Without treatment, it can last for days. Systemic effects include tissue necrosis, heart failure, and temporary paralysis. The one piece of practical first aid that actually helps? Hot water immersion — as hot as you can tolerate without burning yourself. The venom has heat-sensitive components that break down at high temperatures, so the hot water actually denatures it and provides real pain relief. That’s one of those facts I always make sure to remember when I’m near tropical waters.

Leave a Reply